Browsing through Discharge of a Contract – CA Foundation Law Notes help students to revise the complete subject quickly.

Discharge of a Contract – CA Foundation Business Law Notes

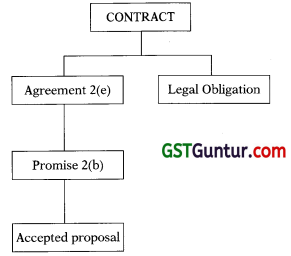

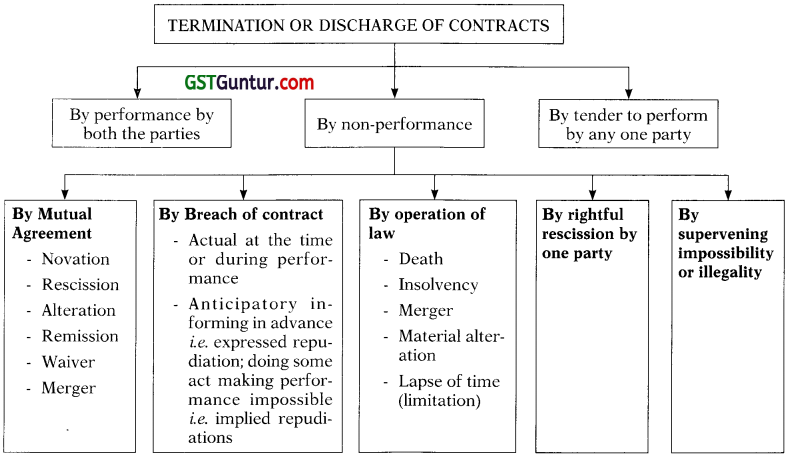

Methods of Termination of Contract:

When the obligations created by a contract come to an end, the contract is said to be discharged or terminated. A contract may be discharged or terminated in any of the following ways:

I. Discharge By Performance:

The obligations of a party to a contract come to an end where he performs his promise. Performance by all the parties, of the respective obligations, put’s an end to the contract completely. This is the normal and natural mode of discharging a contract.

II. Discharge By Attempted Performance:

The offer of performance or tender has the same effect as performance. If a party to a contract offers to perform his promise but the offer is not accepted by the other party, the obligations of the first party are terminated.

III. Discharge By Mutual Agreement:

By agreement of all parties, a contract may be cancelled or its terms altered or a new agreement substituted for it. Whenever any of these things happen, the old contract is terminated. “If the parties to a contract agree to substitute a new contract for it, or to rescind or alter it, the original contract need not be performed.” Sec. 62.

Termination by mutual agreement may occur in any one of the following ways:

A. Novation:

→ Novation occurs when a new contract is substituted for an existing contract either between the same parties or between different parties. The consideration for the new contract is the discharge of the old contract.

- To effect a novation, there must be a valid enforceable new substituted contract.

- Consent of all parties is necessary for novation.

- Novation should take place before the breach or expiry of old contract.

Example:

A is indebted to B and B to C. By mutual agreement B’s debt to C and A’s debt to B is cancelled and C accepts A as his debtor. There is novation. (See Scarf v. Jardine in leading case laws at the end of the chapter)

B. Alteration:

→ Alteration of a contract means change in one or more of the terms of a contract. Alteration is valid if it is done with the consent of all the parties to the contract.

In alteration there is change in the terms of the contract but no change of the parties to it. In novation there may be change of parties.

| Novation: |

Alteration: |

| 1. Novation is substitution of old contract by a new contract by mutual agreement between the parties. |

Alteration means change in the terms of the existing contract by mutual agreement between the parties. |

| 2. The parties may either remain the same or a third party may be introduced. |

Parties remain the same. No third party is involved. |

| 3. Novation rescinds the original contract as a result the original contract need not be performed. |

Alteration does not rescind the original contract. As the same original contract in a modified manner is performed. |

C. Remission:

Remission means acceptance of lesser amount, or lesser degree of performance than what was contracted for in full discharge of the contract.

According to Sec. 63 a party may:

- Dispense with or remit performance wholly or in part

- Extend the time for performance

- Accept any other satisfaction instead of performance

For such a release or promise there no need for consideration or new agreement.

Example:

A owes B ₹ 5,000. A pays to B and B accepts in full satisfaction for the whole debt ₹ 2,000. The old debt is discharged.

A promise by the promise to give concession to the promisor in one or the other form is binding even if without consideration. In Gopala v. Venkata, it was stated that after the remission has been communicated to the promisor and accepted by him, the promise cannot claim the remitted (sacrificed) amount.

D. Accord And Satisfaction:

Under the English law, these terms are used as counter part of the term remission. Under the English Law, “accord” means the promise to accept less than what is due under the original contract. ‘Satisfaction’ means the actual payment or the fulfilment of the smaller obligation.

In the English Law a promisee cannot remit a part of the amount unless a fresh promise is supported by consideration. However, this doctrine of accord and satisfaction as applied in England, has no place in India. Sec.63 clearly states that if the promisee agrees to accept a lesser amount in full satisfaction of the whole claim, this promise is valid and therefore enforceable.

E. Rescission:

Rescission occurs when the parties to a contract agree to dissolve the contract. In the case of rescission only the old contract is cancelled and no new contract comes to exist in its place. The parties come out of the contract by mutual agreement.

F. Waiver:

Waiver means the abandonment of a right. A party to a contract may relinquish (waive) his rights under the contract. Thereupon the other party is released from his obligations. For example, waiver of former’s loan by bank.

G. Merger:

When a superior right and an inferior right coincide and meet in one and the same person, the inferior right vanishes into the superior right. This is known as merger.

Illustration:

→ A man holding property under a lease buys the property. His rights as a lessee vanish. They are merged into the rights of ownership which he has now acquired.

→ A may agree to work as a part-time employee of B. Later, they may decide that A will work as full-time employee.

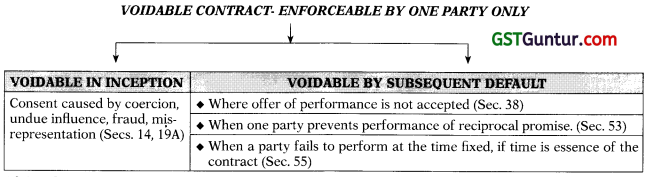

IV. Discharge By Breach of Contract:

When a contract is broken by one party the other party or parties are freed from the obligation of performing the contract. They can also take the remedial measures to which they are entitled. Breach of contract may arise in two ways:

- By actual breach or present breach.

- By anticipatory breach.

A. Actual Breach of Contract:

Actual breach of contract occurs when during the performance of the contract or at the time when the performance of the contract is due, one party either fails or refuses to perform his obligations under the contract. The refusal of performance may be express (i.e. by word or by writing) or implied (i.e. by conduct of the party or by non-action) or abstaining from doing something. D agrees to deliver to B, 5 tons of sugar on 1st June. He fails to do so. There is breach of contract by D.

B. Anticipatory Breach of Contract (Sec. 39) – Anticipatory breach of contract occurs:

→ when a party before the time for performance is due announces that he is not going to perform the contract or,

→ when a party by his own act disables himself from performing the contract.

- C enters into a contract to supply B with certain articles on the 1st June. Before 1st June he informs B that he will not be able to supply the goods.

- X agrees to marry Y. Before the agreed date of marriage, he marries Z.

Consequences of Anticipatory Breach:

When anticipatory breach occurs, the aggrieved party can take the following steps:

(A) May treat the contract as discharged –

- He can treat the contract as discharged, so that he is no longer bound by any obligations under the contract.

- He can immediately adopt the legal remedies available to him for breach of contract, viz., hie a suit for damages or specific performance or injunction.

(B) May not treat the contract as discharged –

Anticipatory breach, by itself, does not discharge the contract. The contract is discharged, when the aggrieved party chooses to treat it as discharged. The aggrieved party may decide not to rescind the contract but to treat the contract as alive and operative and wait for the time of performance. In such a case the consequences are as follows:

- The contract will be operative for the benefit of both the parties. The contract will continue to exist and may even be performed by the other party.

- If the contract is not rescinded and subsequently an event happens which discharges the contract legally (example – a supervening impossibility) the aggrieved party loses his right to sue for damages.

For example, A agrees to supply one ton of sugar to B by 20th August. On 10th August, A informs B that he cannot supply sugar B did not accept the refusal and preferred to wait till 20th August. On 15th August, the Minister declares nationalisation of sugar industry. Now the contract is discharged and B has no remedy against A.

V. Discharge By Operation of Law:

A contract terminates by operation of law in case of death insolvency, and merger.

A. Death:

In contracts involving personal skill or ability, death terminates the contract. In other cases, the rights and liabilities pass on to the legal representatives of the dead man.

B. Insolvency:

When a person is adjudged insolvent, he is discharged from all liabilities incurred prior to his adjudication. Upon insolvency, the rights and liabilities of the insolvent are, with certain * exceptions, transferred to an officer of the court, known as the Official Assignee/Receiver.

C. Merger:

Means coinciding and meeting of inferior and superior right in one and the same person. In such a case, inferior right available to a party under the contract will automatically vanish.

D. Lapse of time:

Contracts may be terminated by lapse of time. In civil suits the obligations and liabilities in contracts are barred by limitation. The provisions of law are stated in the Limitation Act.

E. Unauthorised material alteration:

If the terms of a contract is materially altered by a party to the contract without the consent of the other parties, the contract is discharged and cannot be enforced any more.

VI. Subsequent or Supervening Impossibility – Pre-contractual Impossibility:

A contract which at the time was entered into was impossible to perform, is void ab-initio and creates no rights and obligations. Sec. 56(1) states that “An agreement to do an act impossible in itself is void. “Such fact of impossibility may be –

(i) Known to the parties: In such a case the agreement is void ab-initio and creates no rights and obligations. For example a promise to ride a horse to the Sun or A agrees with B to discover treasure by magic. The agreement is void.

(ii) Unknown to the parties: When both the parties are ignorant of the impossibility at the time of making the contract, the contract, is void on the ground of mutual mistake. For example: A agrees to sell his horse to B but unknown to both the parties the horse had already died at the time of making the contract. The contract is void.

(iii) Known only to the promisor: On the contrary, if the promisor alone knew about the impossibility of performance at the time of making the contract, he shall have to compensate the promisee for any loss which such promisee sustains through the non-performance of the promise. [Sec. 56(3)]

Post-contractual Impossibility:

A contract, which at the time was entered into, was capable of being performed may subsequently become impossible to perform or unlawful. In such cases the contract becomes void. This is known as the doctrine of Supervening Impossibility.

It is also known as the Doctrine of Frustration. Frustration occurs where it is established that due to subsequent change in circumstances, the contract has become impossible to perform or it has been deprived of its commercial purpose.

“A contract to do an act which, after the contract is made, becomes impossible, or, by reason of some event which the promisor could not prevent, unlawful, becomes void when the act becomes impossible or unlawful”.

Grounds of Frustration:

Supervening impossibility may occur in many ways, some of which are explained below:

(i) Destruction of the subject matter of contract – On the destruction of the subject matter, a contract is discharged and no party is liable to perform.

(ii) Change of Law – The performance of a contract may become unlawful by a subsequent change of law. In such cases, the original contract becomes void.

(iii) Failure of pre-conditions – When a contract is entered into on the basis of the continued existence of a certain state of things, the contract is discharged if the state of things change.

→ Illustration: A & B contract to marry each other. Before the time fixed for the marriage, A goes mad. The contract becomes void.

→ Illustration: H hired a room from K for two days with the object (as both parties know) of using the room to view the coronation procession of Edward VII although the contract continued no reference to the procession. Owing to the king’s illness the procession was abandoned. Held, that the contract was discharged and H was excused from paying rent of the room as the existence of the procession was the basis of the agreement.

(iv) Death or incapacity for personal services:

Where the personal qualification of a party is the basis of the contract the contract is dis¬charged in cases of death or personal incapacity. G contracts to act of a theatre for six months in consideration of a sum paid in advance by H. On several occasions G is too ill to act. The contract to act on these occasions becomes void.

(v) Outbreak of war:

A contract entered into during war with an alien enemy is void ab-initio. A contract entered into before the war commenced between citizens of countries subsequently at war, remains suspended during the pendency of the war. After the termination of the war, the contract revives and may be enforced.

Exceptions:

Impossibility of performance, is, as a rule, not an excuse from performance. Only physical or legal impossibility will excuse the parties. The performance of the contract should have become impossible due to any of the circumstances mentioned above.

The doctrine of frustration or supervening impossibility does not apply in the following cases. i.e. in these cases the contract is not discharged.

1. Difficulty of performance – Difficulty does not excuse performance of contract:

The contract will not be affected if performance has become difficult because of disruption of traffic routes. In the case of Tsakiroglou & Co v. Noblee Thori (1962) AC 93, the closure of Suez Canal in 1956 because of outbreak of war there had caused problems in completion of many contracts involving transportation via the Suez Canal. But, the judicial view was that unless it could be proved that transport via Suez Canal was an express or implied term of the contract, its closure could not be said to make the contract impossible.

2. Commercial Impossibility:

A wholesale dealer’s contract to deliver goods is not discharged because a manufacturer has not produced the goods concerned. Similarly increase of wages of prices of raw materials, unseasonable weather or lack of adequate profits do not excuse performance. The reason is that if the parties did not stipulate to the contrary, they must have intended to take the risk of occurrences like these.

3. Strikes, lock-outs, civil disturbances and riots:

These events do not terminate contracts unless there is a clause in the contract providing that in such cases the contract is not be performed or that the time of performance is to be extended.

4. Failure of one of the objects:

When there are several purposes for which a contract is entered into, failure of one of the objects does not terminate the contract.

The Doctrine of Frustration:

When the common object of a contract can no longer be carried out, the court may declare the contract to be at an end. This is known as the Doctrine of frustration. Anson says: “Most legal systems make provisions for the discharge of a contract where, subsequent to its formation, a change of circumstances renders the contract legally or physically impossible of performance.’’

In Satyabharata Ghosh v. Mugniram Bengur AIR(1954) S.C. 44: The Supreme Court of India discussed the English cases relating to frustration and came to the following conclusions:

The doctrine of frustration of contract comes into play when a contract becomes impossible of performance, after it is made, on account of circumstances beyond the control of the parties. It comes within the purview of Sec. 56 of the Indian Contract Act. The word ‘impossible’ in this section | has not been used in the sense of physical or literal impossibility.

The performance of an act may not be literally impossible but it may be impracticable and useless from the point of view of the object and purpose which the parties had in view; and if an untoward event or change of circumstances totally upsets the very foundation upon which the parties rested their bargain, it can be said that the promisor finds it impossible to do the act which he promised to do.

“A contract to do an act which, after the contract is made, becomes impossible, or, by reason : of some event which the promisor could not prevent, unlawful, becomes void when the act becomes impossible or unlawful”.

Grounds of frustration of contract and supervening impossibility are similar. The effect of frustration – Frustration automatically discharges a contract from the date of the frustrating event.

Remedies For Breach of Contract:

I. Rescission of the contract:

When there is a breach of contract by one party, the other party may rescind the contract and need not perform his part of obligations under the contract. This is called the right of rescission which means a right to cancel or to set aside (i.e., reject) the contract.

Further, section 75 provides that a person who rightfully rescinds a contract is entitled to compensation for any damages which he has sustained through the non fulfilment of the contract.

A contracts to supply 100 Kg. of tea leaves to B on 25 April. If A does not supply the tea leaves on the appointed day, B need not pay the price. B may also file a ‘suit for rescission’ and claim damages.

II. Suit for damages:

Damages are the monetary compensation allowed by a court of law to the aggrieved party for the loss or injury suffered by him. The loss or injury suffered is known as damage. This is the difference between “Damage” and “Damages”.

The foundation of modern law of damages in India is based on the judgment in a case of Hadley v. Baxendale (1854) 9E. 341, and is incorporated in sec.73 of the Indian Contract Act.

H’s mill was stopped by a breakage of the crankshaft. He delivered the shaft to B, a common carrier, to take it to the manufacturers at Greenwich as a pattern for a new one. By some neglect on ; the part of B the delivery of the shaft was delayed beyond a reasonable time.

H claimed from B s compensation for the wages of workers and depreciation charges during the period the factory was idle for the delayed delivery and for loss of profits which might have been made if the factory was working. The first two items, were allowed because they were natural consequences of the breach. The last item, loss of profits was disallowed because it was a remote consequence. (Hadley v. Baxendale).

Compensation For Loss or Damage Caused By Breach of Contract: (Sec. 73):

→ “When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by such breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby, which naturally arose in usual course of things from such breach, or which the parties knew, when they made the contract to be likely to result from the breach of it.”

Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach.

Nature:

Damages under the Contract Act are not granted by way of punishment. They are compensatory in nature. The object is to compensate the injured party and bring him on the same position in which he would have been, if there was no breach of contract.

If there is no damage, damages cannot be claimed:

Damages are claimed to compensate any loss or damage caused by breach of contract. If there is no actual loss than damages cannot be claimed. For example, A contracts to buy B’s car for ₹ 60,000/- but breaks his promise. B then sells to C for the same price. B cannot claim any damages Under the law of contract damages are not granted by way of punishment.

Rules:

1. Ordinary damages are recoverable:

Ordinary damages are those which naturally arise in the usual course of things from such breach. They are the natural and probable consequence of the breach, which the aggrieved party suffering can recover from the defaulting party.

2. Special damages are recoverable only if the parties knew about them:

Apart from ordinary damages, special damages can also be claimed. Special damages are for loss which arises on account of the unusual circumstances affecting the plaintiff. They are not recoverable unless the special circumstances were brought to the knowledge of the defendant so that the possibility of the special loss was in the contemplation of the parties.

Thus, special damages are those which result from a breach of contract under some special or unusual circumstances which are in the knowledge of the parties at the time of making the contract.

→ The extent of liability depends upon the knowledge of the parties at the time of the contract about the probable result of the breach.

A, having contracted with B to supply B with 1,000 tons of iron at 100 rupees per ton to be delivered at a stated time, contracts with C for the purchase of 1,000 tons of iron at 80 rupees a ton, telling C that he does so for the purpose of performing his contract with B. C fails to perform his contract with A, who cannot procure other iron and B, in consequence, rescinds the contract. C must pay to A 20,000 rupees being the profit which A would have made by the performance of his contract with B.

→ Compensation is recoverable for:

- Damages arising naturally in the usual course of things.

- Damages arising out of special circumstances in contemplation of parties.

3. Remote or indirect damages are not recoverable:

Damages cannot be claimed for any remote or indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach. Remote damages are those which are not reasonably foreseeable. The party breaking the contract shall not make compensation in respect of loss or damage indirectly or remotely caused.

For example, A contracts to pay a sum of money to B on a day specified. A does not pay the money on that day. B in consequence of not receiving the money on that day, is unable to pay his debts and is totally ruined. A is not liable to make good B anything except the principal sum he contracted to pay together with interest up to the day of payment. This is so because B’s total ruination is an indirect loss.

Nominal damages for no loss suffered:

Where the injured party has not in fact suffered any loss by reason of the breach of a contract, the damages recoverable by him are nominal, i.e., very small. For example a rupee or cent. These damages merely acknowledge that the plaintiff has proved his case and won. In Charter v. Sullivan, the defendant refused to buy a car from the plaintiff which was sold to another customer and no loss was occasioned. He was, thus, held entitled to only nominal damages and not for any loss of profits.

Vindictive or exemplary damages:

Damages for breach of contract are given by way of compensation for loss suffered, and not by way of punishment for wrong inflicted. Hence, ‘vindictive’ or ‘exemplary’ damages have no place in the law of contract because they are punitive by nature. But in case of (a) breach of a promise to marry, and (b) dishonour of a cheque by a banker wrongfully when he possesses sufficient funds to the credit of the customer, the Court may award exemplary damages.

Other Heads for Damages:

- Damages for inconvenience caused by breach.

- Damages for mental pain and suffering. In a Scottish case, a photographer who agreed to take photographs at a wedding, failed in breach of his contract to appear there. As a result the bride had no photographs of her wedding. She was allowed damages for resulting injury to her feelings.

- Damages for pre-contract and wasted expenditure.

- Damages for delay in delivery.

4. Defaulting party liable to compensate as per market price.

5. Such damages are also payable in case of breach of a quasi-contract too.

6. It is the duty of the injured party to minimise the damage suffered.

7. The injured party is entitled to get the costs of getting the decree for damages from the de-faulter party.

8. Liquidated Damages and Penalty:

Liquidated Damages: Where the party fixes a genuine pre-estimate of the probable damage, it is called liquidated damages. Liquidated damages are pre-determined damages agreed at the time of contract, which are considered reasonable by both the parties. It is a genuine estimate of the actual loss or damage likely to be suffered by the aggrieved party.

Penalty:

Where the sum fixed before-hand for the breach of contract does not bear the relationship to the actual damage which the aggrieved party is likely to suffer in the event j of actual breach of contract, it is called penalty. Such an amount acts as a deterrent from committing a breach of contract.

A contract sometimes contains a clause in which a sum of money is named as the amount payable f in case of breach of contract. According to English law, the amount of money payable is interpreted either as liquidated damages or as a penalty.

It is considered to be liquidated damages when the amount is fixed by the parties on the basis of a reasonable estimate of the probable actual loss , which a party will suffer in case of breach. On the other hand, the amount fixed is considered to be a penalty if it is not based upon a reasonable calculation of actual loss but is fixed by way of punishment and as a threat. A penalty will not be enforced by the Court.

In India, the distinction between liquidated damages and penalty is not recognised. Sec. 74 of the Contract Act which deals with pre-determined damages, lays down that if the parties have fixed what the damages will be, the courts will never allow more. But the court may allow less. A decree vis to be passed only for reasonable compensation, not exceeding the sum named by the parties.

Thus, section 74 makes no distinction between a liquidated damages and penalty and the aggrieved party is entitled to reasonable compensation not exceeding the amount so named, regardless whether it is penalty or not.

Under section 73, the actual loss or damage has to be proved but under section 74, the proof of actual loss or damage is not essential.

The difference between the liquidated damages and penalty depends on the facts and circumstances of each case and the intention of the parties which is to be gathered from the whole contract:

→ If the intention is to secure performance of The contract by imposition of a fine or penalty, the sum specified is penalty; but if on the other hand, the intention is to assess the damages for breach of contract, it is liquidated damages.

→ Liquidated damages are the amount assessed on the basis of actual or probable loss by both the parties. Penalty is not based on actual or probable loss. Penalty is payable in the event of breach with a view to prevent a party from committing breach.

→ Liquidated damages are imposed by way of compensation. Penalty is imposed by way of punishment. The amount of penalty is exorbitant, extravagant and unconscionable.

→ Courts in England usually allow liquidated damages without any regard to the actual loss sustained and treat penalty clause as invalid. But under the Indian law, section 74 of the Contract

Act does not recognize any difference between liquidated damages and penalty. The courts are required to allow reasonable compensation so as to cover the actual loss sustained, not exceeding the amount so mentioned in the contract.

A stipulation for higher rate – from the date of default may be taken as a penalty if the enhanced rate is exorbitant. If it is reasonable, then, it shall be allowed. The leading case on the matter is Mackintosh v. Crow (1883) 9 Cal 689. If the normal rate of interest is fixed at 12% and the rate of interest from the date of default is to be 36%, this may be taken by court as very unreasonable and may be reduced.

Earnest Money and Security Deposit:

Sometimes, when a contract is formed, one party gives to the other a sum as a deposit. This deposit may take two forms: earnest money and security deposit. Earnest money is a kind of advance payment of price by one party to the other out of a larger amount payable.

B agrees to buy goods from C and pays him Rs. 5,000 in advance as earnest money. This amount shall be adjusted against the total price payable by B to C. The earnest money paid may or may not be liable to be forfeited under the contract if buyer breaks the contract.

Security deposit – is a payment made as a guarantee that the contract shall be fulfilled by the person who has paid the deposit. If the contract is not fulfilled, then, the deposit shall be forfeited under the contract.

Where a buyer has paid earnest money which is liable to be forfeited if buyer breaks the contract, then, on the contract being broken by him, the seller may forfeit the amount if it is a reasonable amount (Shree Hanuman Cotton Mills v. Tata Aircraft Ltd. [1969] 3 SCC 522).

III. Suit For Specific Performance of The Contract:

There are cases where the damage or loss suffered cannot be measured in terms of money. The jj court, may, in such cases where the ordinary remedy by a claim for damages is not adequate y- compensation, direct the defaulting party to perform the contract specifically. (Under Sec. 12. of if; the Specific Relief Act, 1963).

Specific performance is an order of the Court directing the defendant to fulfil his obligations under the contract. Specific performance is a discretionary remedy and is ® only available where damages are not an adequate remedy.

Some of the cases where specific performance is ordered by the court are:

- Where the act itself is such that monetary relief for its non-performance is not adequate.

- Where no standard is available to ascertain the value of the actual damage caused by non-performance.

- Where it is not probable that the compensation money will be available.

Examples:

The specific performance is granted in contracts connected with land, buildings, rare articles and unique goods having special value etc. because injured party will not be able to get an exact substitute in the market.

Specific performance is not allowed in the following cases:

- Where monetary compensation is an adequate relief.

- Where the contract is of personal nature, example – a contract to marry or a contract to paint a picture or,

- Where it is not possible for the court to supervise the performance of the contract example – a building contract.

- Where one of the parties to the contract is not competent to contract like a minor.

IV. Suit For An Injunction:

‘Injunction’ is an order of a court restraining a person from doing a particular act. It is a mode of securing the specific performance of the negative terms of the contract. To put it differently, where a party is in breach of a negative term of the contract (i.e, where he is doing something which he promised not to do); the court may, by issuing an injunction, restrain him from doing what he promised not do so. Thus ‘injunction’ is a preventive relief. It is particularly appropriate in case ‘anticipatory breach of contract’ where damages would not be an adequate relief.

N, a him actress agreed to act exclusively for Warner Bros, for one year. During the year she contracted to act for X. Held, she could be restrained by an injunction from acting for X. Warns Bros. v. Nelson. It is to be noted that in this case an order directing N to act for Warner Bros. (Specific performance of the contract) was not passed because the contract was of a personal nature and performance could not have been supervised by the courts.

V. Suit For Quantum Meruit:

Quantum Meruit means ‘as much as merits ‘or ‘as much as deserves or earns’. In legal sense, it means ‘payment in proportion to the work done’. In other words, quantum meruit means that a person can recover compensation in proportion to the work done or service rendered by him.

Normally, a person cannot claim performance from the other party, unless he has performed his obligation in full. But under the claim of quantum meruit, a person who has performed some work can claim payment in proportion to the work done.

The right to claim quantum meruit is not conferred by the contract but it is conferred by the law. It is quasi-contractual in nature. This right is not similar to that of the damages, which arises out of the contract. Two things should be noted.

→ The claim for quantum meruit can be made only when the original contract has been discharged. If the original contract exists, the party who has done something for the other party cannot have quantum meruit remedy but he is to rely on the remedy in damages, and

→ Generally, the party who is not in default should bring the claim for quantum meruit.

The claim on quantum meruit arises in the following cases:

→ Where there is breach of the contract

Where a party performs a part of the contract, but the other party breaks it in between, then the injured party can claim compensation for the work done or the service rendered.

(i) A agreed to write an article for B. The article was to be published in instalments. After 3 instalments were published, the magazine was closed. Can A claim on the basis of quantum meruit?

Answer:

Yes, Example (Planche v. Colburn).

(ii) A boy was engaged for a complete journey against a lump sum payment of ₹ 500. The boy died before the journey was completed. Can his legal representatives claim the amount? Can a claim on the basis of quantum meruit arise in this case?

Answer:

No, as the contract is not divisible. (Cutter v. Powell).

2. When an agreement is discovered to be void:

Where some work has been done and accepted under a contract which is subsequently dis-covered to be void, then the person who has performed the part of the contract is entitled to recover the amount for the work done. (Sec. 65)

Example:

C was appointed as ‘managing director’ of a company at certain remuneration, by the board of directors. Subsequently it was discovered that the board was not qualihed to make this appointment and hence it was void C, in the meantime, rendered services to the company. He sued the company for remuneration for the period he provided services. The court held that C could recover on ‘Quantum Meruit’ – [Craven Ellis v. Canons Ltd. [1936] 2 K.B. 403]

3. When something has been done non-gratuitously:

When something has been done non-gratuitously: i.e., has been done with the intention of getting payment. (Sec. 70)

4. Where work has been done by the person guilty of breaking the contract:

In such a case defaulting party would be liable for consequences of breach, but for the work done by him he may be entitled to get payment in the following circumstances:

→ Where the work to be done was divisible:

A contract is divisible and a party performs a part of it and refuses to perform the remaining part, the defaulting party can claim reasonable compensation for the part performed, on the basis of quantum meruit. Thus two conditions should exist:

- If the contract is divisible and

- If the party not at fault has enjoyed the benefit of part performance.

Example:

A. agreed to supply 1000 bales of cotton to B @ ₹ 1000 per bale. The bales were to be supplied in two instalments of 500 each. A supplied the first instalments but failed to supply the second. B must pay for 500 bales.

On the other hand, if the contract is not divisible, i.e., it requires complete performance as a condition for payment, the party in default cannot claim payments for work done, on the basis of quantum meruit.

5. When the indivisible contract is performed substantially/fully:

If a lump sum is to be paid for the completion of the entire work and the work has been completed in full, though badly, the person who has performed the contract can claim the lump sum; but the other party can also claim a deduction for bad work.

Example:

A agreed to do decorate the flat of B for ₹ 1,00,000. The work was done but B complained of faulty workmanship. It was estimated that it could be rectified by spending ₹ 30,000 more. It was held that B could adjust this amount from the total amount due (of ₹ 1,00,000).